published: 7 June 2024

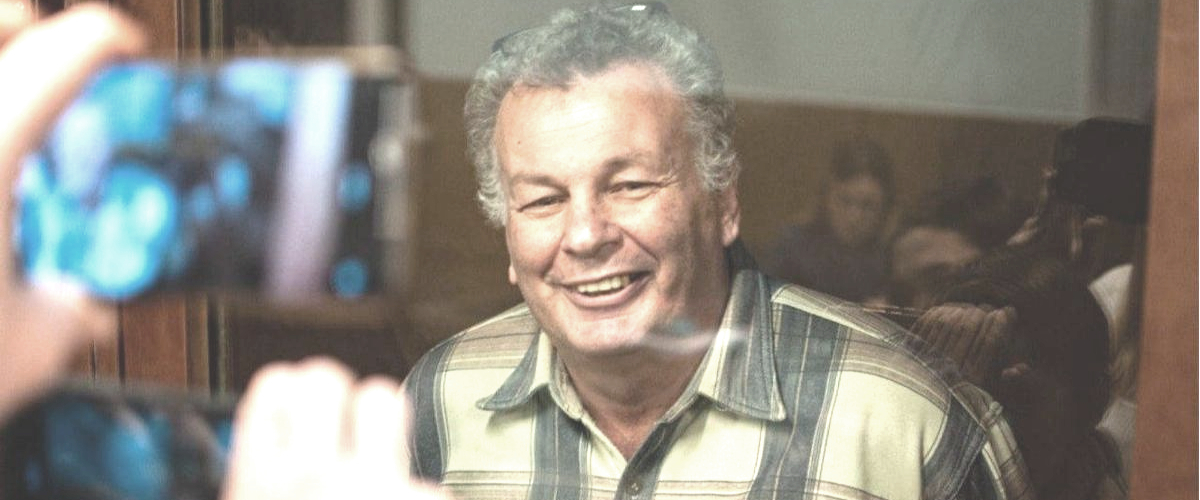

Political prisoner in Russia: Michael Krieger, antiwar and pro-Ukraine activist

Activist Mikhail Krieger, member of the Soldarnost movement and the board of Moscow Region Memorial, has been detained since November 3, 2022. He was sentenced to seven years of penal colony for posts on social media.

Who is Mikhail Krieger and why he was imprisoned?

Mikhail Krieger has been an active member of the democratic and human rights movement since the late 1980s. He was a member of the “Solidarnost” movement since its founding in 2008, and is a board member of Memorial’s Moscow regional branch. Mikhail was originally trained as an excavator operator. He later ran a construction equipment rental business. Prior to his detainment and conviction, he was delivering groceries using his own vehicle.

Mikhail Krieger organized campaigns in support of political prisoners, protested against Russia’s wars in Chechnya and Ukraine, helped refugees, and was a member of the Anti-War Action Committee in the 2000s. From the 2000s onwards, he was repeatedly detained at peaceful protests and sentenced to fines and administrative arrests. In February 2022, Krieger was arrested at an anti-war rally, and detained again twice that same year – the reason being that he had put stickers endorsing Alexei Navalny on his car (both times Mikhail was sentenced to ten days in custody, allegedly for disobeying the police).

In November 2022, Russia’s Investigative Committee opened a case against Krieger on charges of “justifying terrorism” based on a Facebook post published two years prior. The publication mentioned Mikhail Zhlobitsky, an anarchist who had committed a suicide bombing against an FSB facility in Arkhangelsk in 2018. Krieger was sent to a pre-trial detention center. Soon the investigation added another charge: “inciting hatred or enmity towards a social group,” as well as an additional count of “justifying terrorism” in relation to another Facebook post.

On May 17, 2023, Moscow’s 2nd Western District Military Court sentenced Mikhail Krieger to seven years in a general regime penal colony. In October that year, the Military Court of Appeal sustained the verdict.

The human rights project “Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial” recognizes Mikhail Krieger as a political prisoner. He is currently detained in the IK-5 penal colony in the village of Naryshkino in the Orel region.

What are the charges against Mikhail Krieger?

Mikhail Krieger was detained on November 3, 2022, in the center of Moscow, near a restaurant to which he was delivering groceries. His apartment was then searched, and he was brought in for questioning by the Investigative Committee.

On November 4, 2022, the Investigative Committee opened a criminal investigation against Krieger on charges of justification of terrorism (Article 205.2, Part 2 of the Russian Criminal Code). The investigation was entrusted to a seven-strong team for highly important cases.

On November 6, 2022, Moscow’s Cheremushkinsky District Court placed him under arrest for two months. Neither journalists nor Krieger's relatives were allowed to attend the trial hearing, despite the motions filed by his lawyers and the fact that the trial had not been formally declared closed to the public. The judge's explanation was that the hearing was held on a weekend.

On January 12, 2023, the investigation added a new charge, “incitement to hatred or enmity” (Article 282 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) and a second count of “justification of terrorism.”

On the first count, the investigation charged Krieger for a post published in 2020 on a Facebook page titled “Mikhail Krieger.”

The post spoke of the harsh sentence handed out to a married couple from Kaliningrad, accused of state treason, a decision that caused a backlash in the media. The text was a comment about the reposting of a Vedomosti article about the verdict. Commenting on the verdict, the author wrote:

It’s safe to say that in our country, Cheka monsters have seized power over people. And they are eating people, munching and crunching on them. They are swallowing people whole like a boa constrictor does a rabbit. ...We are going through selective breeding, when only those who keep silent survive, those who keep their mouths shut just in case. And we can already ascertain that these monsters have crushed society. They have defeated the people. They've broken the backbone of society, completely crushed the will to resist. And people are becoming – have become – voiceless cattle who rejoice when today it is their neighbor’s turn to be dragged to the slaughterhouse, and not theirs yet.

The investigation based the charges on the final paragraph, which was cited in the text of the indictment:

That’s why Mikhail Zhlobitsky is, to me, a hero. He had the courage to hold his ground. And maybe also the guy who started a shooting at [the FSB headquarters] on Cheka Day [December 20, officially “Security Service Officers Day”] a year ago. These bandits don't understand any other way. It’s useless to try talking to them, as useless as talking a boa constrictor out of swallowing a rabbit. And I didn't follow the example of these people myself just out of my own weakness. Don’t bother bringing up mercy, non-violence, or innocent victims... These monsters didn't even announce a war on people, but mere battering. And well, war is war.

According to the investigation, this text “contains a number of linguistic and psychological markers implying that it condones the activities of M. Zhlobitsky – destructive, violent actions (an explosion creating a death risk) committed on October 31, 2018, ... the commission of violent acts by E. Manyurov against employees of the [FSB] on December 19, 2019.” The inclusion of Evgeny Manyurov in the charge is based on the vague reference to “the guy who started a shooting on Cheka Day.”

For the same post, Krieger was charged with “inciting hatred and hostility with the threat of violence” against a social group, “employees of Russia’s Federal Security Service.” However, the court reevaluated the actions Mikhail was incriminated for and instead of “inciting hatred” found that the text contained “calls to extremism” (Part 2 of Article 282 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

The ground for the second charge on Article 205 was, in the investigation’s own words, about justifying “an attempt on the life (murder by hanging) of a government official, the President of Russia V.V. Pu..n, in order to seize his governing and/or political activities and as an act of vengeance for such activities.” The indictment is based on the 2019 publication:

Dear friends, those who are concerned with the excessive “blatancy” I express towards certain people. Thank you all very much for your care. But I've spoken enough already. And I am not willing to conceal my raging hate towards the regime, the Chekists who established it, and personally towards Vladimir Putin. And believe me, when and if I live to see these KGB cockroaches being hanged, I will do everything in my power to participate in such an uplifting event.

Grounds to consider Krieger a political prisoner

The project “Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial” notes that, regardless of the authorship, the quoted posts in and of themselves do not provide grounds for criminal prosecution, let alone imprisonment.

Russia is not the only state to recognize the endorsement of terrorism as a criminal offense. Such an offense is a particular case of inciting hate-motivated violence, and international law has issued recommendations on how to respond to such offenses. One document addressing this issue is the Rabat Plan of Action on “the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to hostility, discrimination or violence,” developed by international experts with the support of the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR). However, the Rabat Plan calls for putting a higher threshold on restricting freedom of opinion and, in identifying incitement of hatred, to take into account the context of particular statements, carefully analyze their contents, and assess the risks of potential harm as well as the existence of an intent.

The context in which Zhlobitsky was mentioned is a publication referring to the court verdict on the “Kaliningrad case” of state treason, which the author sees as another example of the categorical and continuous infringement of civil liberties in Russia. The condemnation of these vicious practices perpetrated by the state (in particular, the lack of judicial independence and the abuse thereof as a punitive force targeting dissenters by the state) is at the core of the commentary for which Krieger is prosecuted.

According to the note to Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, “justification of terrorism” is understood as “a public statement deeming terrorist ideology and practice as correct, in need of support and following.” However, the first text imputed to Krieger does not call for any violent or terrorist acts: it presents the author's opinion on the events mentioned and his assessment of the situation that shaped the background of the actions of Zhlobitsky (and possibly Manyurov). Leaving aside the controversial characterization of their actions as terrorism, the post does not argue that their actions are “correct, in need of support and following.”

Moreover, Krieger points out that he is personally not capable of violent acts. Mikhail Krieger has been consistent in his belief in peaceful and lawful forms of fighting for his rights. There are numerous videos found online of Krieger being detained at demonstrations and pickets. They show that he did not engage in any physical confrontation with police, and had only resisted unlawful detentions passively, if at all.

As for the second imputed text referring to Vladimir Putin, the investigation once again fails to consider the specific context in which the reference appears. In no way does the text imply that the hypothetical execution of Putin should be carried out via a terrorist act. On the contrary, if the context of his other statements and opinions were to be taken into account, as Krieger has repeatedly argued on his social media, putting Putin on legal trial to be plausible and desirable. He also discussed the possible accusations to be brought up by such a trial. In that case, the hypothetical execution mentioned is in no way an offense under Article 277 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (as the investigation insists), but rather the implementation of a lawfully issued sentence. Krieger's use of the phrases “when and if I live to see it”; “I will fight for the right” emphasizes that should such an event occur in the future, it would have occurred as a result of circumstances beyond his control.

Laying charges of such nature does not arise from law, but is rather driven by an intent to sacralize and protect Putin's image from lèse-majesté. A striking example of this issue is the very text of the indictment, in which the investigator hesitates to spell out Putin's name, replacing it with “Pu...n.”

Thus, the investigation and the court use a very relaxed interpretation of “justification of terrorism” and deliberately criminalize the defendant. Taking into account the provisions of the presumption of innocence enshrined in Article 49 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation and Article 14 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, the irremovable doubts about the guilt of the accused must be interpreted in his favor.

The risk of the 2 and 3-year-old statements on which Krieger was imputed leading to any tangible consequences is highly doubtful. Therefore, even if we were to agree that the first text actually approves of Zhlobitsky's actions, its public danger is insignificant.

As of June 2024, the human rights monitoring initiative OVD-Info reports on 55 criminal cases of “justification of terrorism” initiated in relation to statements concerning Zhlobitsky's suicide bombing in the Arkhangelsk FSB (including that of Mikhail Krieger). The FSB has used this repressive campaign to suppress an important public debate concerning the dangerous and harmful role of this agency in modern Russia and the criminal methods of the state that often mimic those of the Soviet era.

At the same time, given the high level of scrutiny that security services apply to people taking part in protest movements and the fact that Krieger has long been known to the police as one of the most active participants in street protests, it is hard to imagine that the 2019 and 2020 publications escaped their attention at the time of publication. The criminal case and Krieger’s imprisonment in 2022 appear to be a continuation of the state's campaign to wipe out any expression of dissent from the public space and a reaction to Mikhail Krieger's consistent anti-war and critical stance towards Russia’s current leadership.

As Mikhail himself said in his final plea, he sees the criminal prosecution as a response to his “first anti-war and now pro-Ukrainian stance.” Born in Dnipro (then Dnipropetrovsk) in Ukraine and having spent most of his life in Russia, Krieger continued to criticize Russia's military aggression throughout the proceedings.

This [prosecution] is a response to me showing up at public protests with anti-war slogans, my aid to Ukrainian refugees, which, I hope, has done at least something to wash away the fratricidal shame in which our country has covered itself.

A detailed argument for Krieger's recognition as a political prisoner is available in Russian at the “Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial” website.