published: 14 February 2025

The Dead Road: the prison history of the polar area where Navalny died

On February 16, 2024, Alexei Navalny was murdered in a prison colony in the settlement of Kharp in the Russian Far North. The history of the area where he spent the last months of his life in torture conditions has long been inextricably linked to prisons and camps. This is the story of Kharp, Labytnangi, Salekhard and the unfinished “dead road” across the tundra.

Transpolar Mainline

The railway from Chum station to Labytnangi station was the first section of the ill-fated Transpolar Mainline, which was supposed to stretch for 1,482 kilometers from Vorkuta to the Yenisei River across the Russian North, but was never completed. The project, three-quarters realized, was stopped immediately after Stalin’s death, and the unfinished railway came to be known as “the Dead Road”. However, a small section from Chum to Labytnangi, constructed between 1947-49, remains in operation. Kharp station, some 30 kilometers away from Labytnangi, is served by this line.

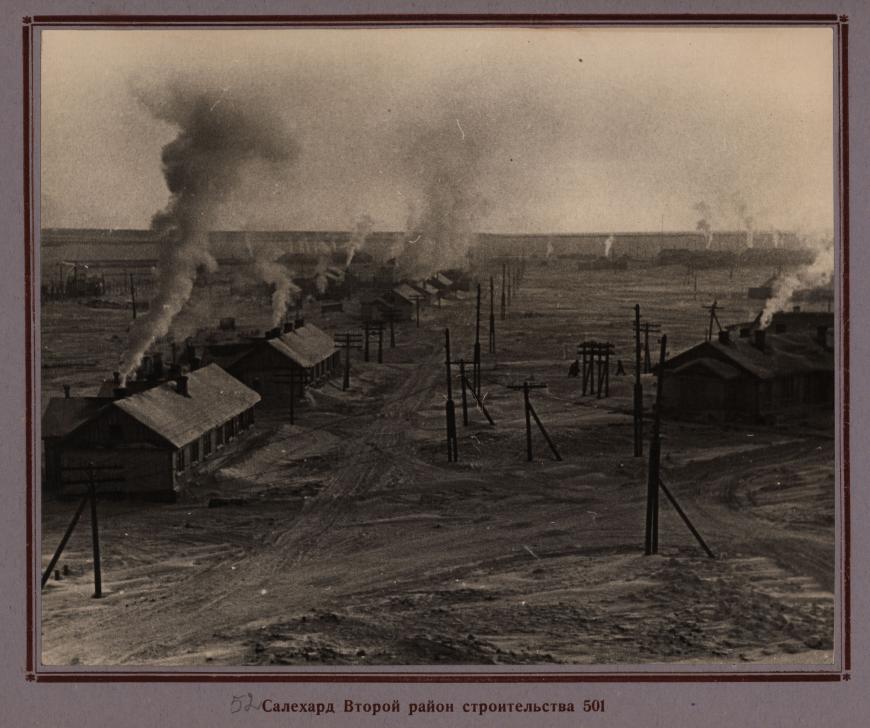

It should be said that the original project, approved by Stalin in December 1946, was much more modest, although still quite ambitious. The road was to pass through the Ural Mountains, connecting the western and eastern Polar Regions, and then turn upward to Yamal Peninsula. A seaport was to be constructed somewhere on the way, in the Gulf of Ob. The purpose of the construction was never publicly explained, but it was most likely strategic - the seaport was needed to protect the northern coast, the vulnerability of which had been exposed by the recent war. “Construction Project 501” was established by Stalin’s personal order in February 1947 along with the Northern Railway Construction Administration within the Gulag system, which immediately saw an influx of prisoners transferred from the Vorkuta and Pechora camps.

The project was personally supervised by the then Minister of the Ministry of Internal Affairs Kruglov, who made regular reports to Stalin, Prime Minister Malenkov and his deputy Lavrenty Beria, himself formerly in charge of Gulag administration. It advanced at a staggering pace: construction began in April 1947, mere two months after the exploration expedition was sent out, and by the end of the year 118 kilometres had already been built. While the hastily transferred prisoners were building the Ural section, the prospectors searched feverishly for a place for a seaport on the coast of the Gulf of Ob. Shaky ground and shallow water all along the shore made the task extremely difficult. The Russian name Cape Kamenny, “Rock Cape”, may have misled them into hoping for a solid shore. It turned out to be a mistranslation from Nenets: the first map-makers heard the word “pae” (“crooked”) as “pai” (“rock”). Construction of the port began without making sure that the coast was secure and the bay was deep enough, and the first ship that tried to dock at this place ran aground and sank. However, the transferring of workers and equipment continued for months after the accident until the supervisors finally recognized the task as impossible. The construction of the railway’s second section from Obskaya station to Cape Kamenny, which had already begun, had to be urgently curtailed.

A failure can always be disguised as a change of plans, and a new project was immediately announced, which was even more ambitious, expensive and complex: extending the line through the Polar Region to the port Igarka in the mouth of the Yenisei river. The problem was that Salekhard, the initial point of the new line, was separated by the Ob river from Labytnangi, the terminus of the first section…

Constructing a bridge to connect the two sections would be an expensive and complex endeavor and thus a temporary train crossing was set up: by ferry in summertime and by ice crossing during the winter months. It remains the only way to cross the river by automobile to this day.

The Transpolar Mainline ultimately led to nothing but lost human lives, environmental damage and billions of rubles wasted for no good reason during the time of the postwar hunger and devastation.

Testimonies of the prisoners of the Project 501

Lazar Shereshevsky (1926–2008):

In the spring of 1947, news spread in the camps located in central Russia that some grandiose construction project was being planned in the Far North, where they were inviting volunteers among prisoners… The idea of captive “volunteers” would seem atrocious. But it was indeed the case that prisoners were offered to express their willingness to go to a new project, which many did express. Those who agreed were promised term reductions! It meant that, on the condition of meeting working targets and respecting the rules, one day was to be counted as a day and a half or even two days! A sentence could be halved in such a way… Lack of information, however, was frightening. Regular groups of prisoners who had just been sentenced were arriving along with the volunteers… In February 1948, I went to the Krasnaya Presnya transfer prison, in a group of my inmates and a few dozen other political prisoners, to be sent to the mysterious northern site, and I was no volunteer. The project was shrouded in secrecy and advanced in a hasted fashion. People with shovels, wheelbarrows, picks, crowbars were driven out to load, lay, level the embankment, working in columns along the future roadbed at a distance of several kilometers between the crews. The permafrost and shaky soil were doing their job every minute: they eroded, sucked up, spoiled the future road, stubbornly resisting human intrusion.

(Lazar Shereshevsky. The Dead Road. Memories of a Former Prisoner. Gudok, 12.03.1989)

Valentina Ievleva (b. 1928):

We arrived in Labytnangi. The local authorities welcomed us by urging us to fulfill the tasks set by the country. We were to begin construction of a railway to the Kara Gate. I stayed five days at the transfer station in Labytnangi. Then we were loaded onto barges and transported across the Ob. It was late fall. They brought us to the tundra. There was a snowy expanse all around. A dozen tents were set up where we were to live. In the morning, after inspection, we received our work assignments and were equipped with picks and shovels. The ground was already frozen, it was hard to dig. The North met us with bad weather. Tired, we returned from work to the stoves that were burning inside the tents day and night. When I went to bed, my legs were warm, as the stove was red hot, and my hair was covered with frost. Sleeping was impossible without headwear. There was frost on the tent walls. We couldn’t bathe for a month, resulting in a lice infestation. I’ll never forget how we used to flick the big, white lice in front of the stove. They were mostly in the seams. I'd never seen such lice before. I rebelled again, refusing to work. Suddenly, a work order on my name. I was taken to the ward, there the jailer was replaced by a convoy. A few people gathered, and we were taken to Salekhard - some to be released, some to be tried, some to the infirmary, and I was assigned to the theater. I felt joy knowing that I was going to be doing the work I love.

(Valentina Ievleva. Life Unkempt // Memories of Gulag)

Salekhard

The oldest city in polar Siberia was founded in the late 16th century as the Obdorsk stockade. Obdorsk was a place of brutal northern exile in the Russian Empire. The Soviet authorities changed the city’s name in 1933 to Salekhard (“settlement on the cape” from Nenets) but not its purpose, as it became one of the largest hubs of the Gulag system. It was here that the Northern Railway Construction Administration and the Ob Camp Administration initially headquartered.

In the city itself there were several camp stations, a camp theater (moved to Igarka in 1950), an infant home for children born in detention. The city was especially changed by new construction plans in 1949 - Salekhard was to become an important railway hub. These plans collapsed together with the Transpolar Mainline project, but the legacy of those years is still present. After the abolition of the camp system, the neighborhood of Salekhard remained one of the places where the prison-camp history was not interrupted, but continued.

Labytnangi

The Khanty settlement at the site of the present-day town of Labytnangi (“seven larches”) has been known since the middle of the 19th century. The Soviet authorities established a collective farm there in the early 1920s. But the biggest changes came in 1948, when it became a site of a camp for prisoner workers and the terminus of the Chum-Labytnangi train line, which was never continued either to the North or to the East. The railway station with trains going beyond the Urals, on the one side, and the crossing of the Ob River to Salekhard on the other made it the most important transport hub for the region. There is no bridge between Salekhard and Labytnangi, although the idea has been discussed with varying degrees of intensity for the past 80 years. Labytnangi is home to the men’s high-security penal colony known as “Polar Bear”, a direct heir to the Gulag system: it was originally one of the branches of the Vorkuta camp. “Much time has passed since the establishment of the institution, people have changed, and along with them the institution itself has changed its appearance,” the editors of the prison’s website write nostalgically. In 2017-2019, the colony became infamous for housing politically imprisoned Ukrainian filmmaker Oleh Sentsov. After Sentsov’s prolonged hunger strike, which caused an international outcry, he, along with several other Ukrainian political prisoners, was released in exchange and returned to Ukraine.

Kharp

The settlement of Kharp (“northern lights” from Nenets) is located in the foothills of the Ural Mountains, between the Ural Ridge and Siberia. There was no settlement here until 1948. With the construction of the Chum-Labytnangi railway several barracks for construction workers-prisoners were built, then a station and some houses for free railway workers. The camp buildings did not stay abandoned for a long time, like those along the Dead Road. Already in 1961, after the abolition of the Gulag, the camp resumed. It was then that IK-3, a high-security men’s colony, better known now by its unofficial name “Polar Wolf”, was founded in Kharp. The present-day settlement was built by prisoners, who were also engaged in repairing the deteriorating railway tracks. In 1973, the special regime prison IK-18 (“Polar Owl”) was added to IK-3. In 2004, it was designated a colony for those sentenced to life imprisonment, and almost immediately gained infamy for torture. In December 2023, Russian politician and political prisoner Alexei Navalny was transferred to the Polar Wolf colony. On February 16, 2024 Navalny died on its premises. The exact circumstances of his death remain unknown; independent journalists have found out that all evidence, including even snow from the prison yard where Navalny reportedly died, was hastily destroyed. “For many years, the institution has made a significant contribution to the fulfillment of important state tasks for the re-education and correction of convicts, their return to society as law-abiding citizens,” the colony's website reads.