published: 1 September 2025

On the 85th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II

Today is the memorial date of the end of World War II, and we remind of last year’s statement of the MIA Board, it has absolutely not lost its relevance.

This statement is also available in Czech, Lithuanian, German and Polish.

This year, Europe – and not only Europe – will commemorate the 85th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.

In the aftermath of the war, it seemed that humanity would never forget this tragedy and would be able to learn from it. For Russians, the phrase "as long as there is no war" became a kind of proverbial incantation for several generations.

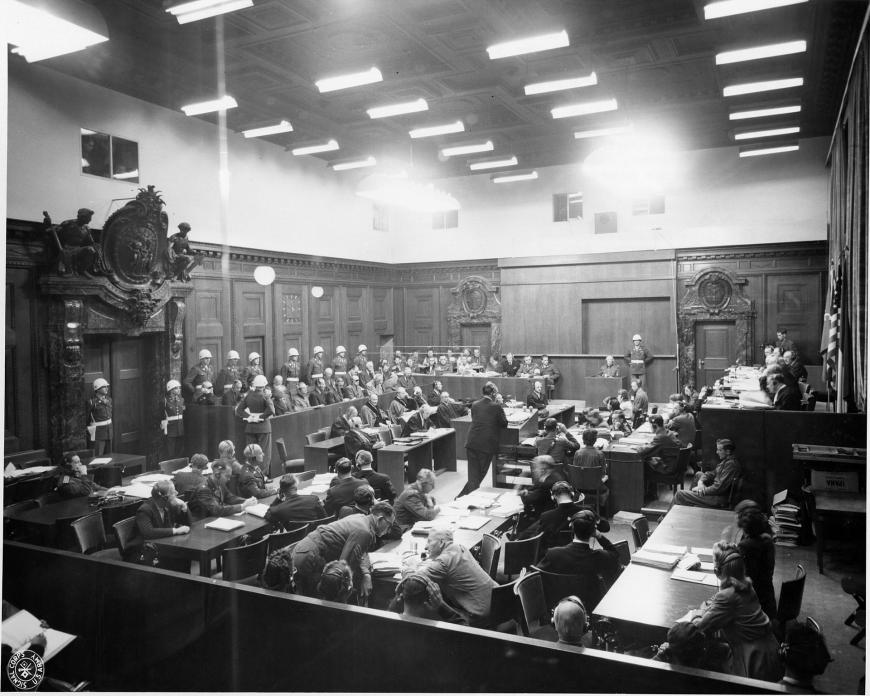

To prevent future conflicts, the United Nations was founded, and international covenants and conventions were adopted. The direct instigators of the war were brought before the Nuremberg Tribunal, whose decisions became an essential part of international law.

It seemed that the era of wars and annexations in Europe had come to an end.

Today, as the generations that survived the war against Nazism have passed away, the immunity to militarism has weakened, if not vanished entirely. With the events of World War II now a part of history, the world is facing the same old threats. A new large-scale war is underway in Europe, and it is being waged by Russia. Russia, which claims to be the successor to the Soviet Union – one of the states that defeated Nazi Germany, established the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal and created the United Nations.

The Memorial Society works with historical memory. And it is clear to us that the aggression against Ukraine was made possible because the current Russian authorities have usurped the past. It is no coincidence that the Russian Historical Society is permanently headed by Sergei Naryshkin, Director of the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation.

The view of history that the Russian authorities are aggressively imposing on society, especially the history of the Second World War, represents an extremely dangerous mixture of aggressive nationalism, sacralization of power, and militaristic psychosis. The ideology of the "Russian world" – the worldview that putinism is trying to instill in the population – paradoxically resembles more and more the ideology with which Hitler set out to conquer Europe 85 years ago.

Increasingly, Russian authorities at various levels are unconsciously (and perhaps in some cases deliberately) reproducing well-known clichés of Nazi propaganda in their rhetoric. For instance, one of Russia's leading politicians proclaims without a shadow of a doubt the slogan "One Country, One President, One Victory" – a slight modification of the Nazi slogan "Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer" – and a sports festival in one of the Russian regions is called "Triumph of the Will," echoing the title of a Nazi propaganda film from 1935.

The Russian president prefaced his aggression against Ukraine with a long "historical" article in which he questioned the very existence of the Ukrainian nation, its language and culture, and its right to independent statehood. This is very similar to the statements made by Nazi leaders about other peoples, and could well be called a theoretical justification for genocide.

No wonder that recently Putin publicly blamed not the aggressor, but its victim for the unleashing of the Second World War:

... It was the Poles who forced it, they played games, and forced Hitler to start the Second World War against them. Why did the war begin with Poland on September 1, 1939? Poland was uncooperative. There was no other choice for Hitler in the realization of his plans [but] to start with Poland.

It is difficult to imagine a statement more incompatible with the verdict of the Nuremberg Tribunal.

At the same time, interpretations of historical events that contradict the official Russian narrative have become grounds for criminal prosecution: for example, drawing parallels between Stalinism and fascism, or pointing out the role played by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in unleashing the war. It is such statements, and not those resembling Putin's discourse, that Russian courts consider a "denial of the facts established by the verdict of the International Military Tribunal" and "rehabilitation of Nazism" (Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

* * *

The question inevitably arises: why were Russian authorities able to usurp history in a country that was relatively free (which Russia was in the 1990s)?

We believe that this happened because the most important issues of Soviet and Russian history never became a subject of broad public discussion and remained unprocessed by public consciousness. At the beginning of Putin's rule, these gaps (we are not talking about gaps in historical knowledge, as there are actually almost none left, but about gaps in mass consciousness) made it possible for the authorities to embark on the path of aggressive political manipulation.

This applies to the events of the Second World War, above all to the premises of the war.

Certainly, the main cause of the war were the aggressive policies of Nazi Germany. The Nuremberg verdict against the former leaders of the Third Reich convicted them of "committing Crimes Against Peace by the planning, preparation, initiation and waging of wars of aggression, which were also wars in violation of international treaties, agreements and assurances".

But for obvious reasons, the Nuremberg Tribunal did not, and could not, consider questions pertaining to the role of prewar policies carried out by the victorious powers in creating the conditions that made World War II possible. Nuremberg was the trial of a specific group of people for specific crimes committed by them. However, these issues cannot be dismissed. They belong to the realm of political morality and, therefore, need to be studied not only by historians but also by society.

When looking at western powers this raises the question of policies of "appeasement of the aggressor" at the expense of the victim of aggression, i.e., the Munich Agreement signed on September 30, 1938. The first victim of this agreement was Czechoslovakia, followed by the United Kingdom and France, who had signed this agreement.

When looking at Moscow, the question revolves first of all around the "Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact" signed on August 23, 1939 - that is, the complicity of the USSR in the aggression. The victims of this pact (primarily its secret protocol on the "delimitation of spheres of interest") were Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, Romania, and finally – the Soviet Union.

The "Munich Betrayal" is often compared to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact - and the comparison is legitimate. Both pacts led to World War II, indirectly in the case of the former and directly in the case of the latter. However, there are two important differences between these agreements.

First, British and French leaders did not seek any territorial gains at Munich. Indeed, their actions, dictated primarily by a ifear of war, were extremely short-sighted – the policy of "appeasement" turned out to be a betrayal of Czechoslovakia and, as time proved, a betrayal of the interests of their own countries as well. Still, it is difficult to call this policy "aggressive".

Secondly, the Munich Agreement was concluded publicly, with no secret protocols attached. Even the territorial claims of Poland and Hungary, which decided to take advantage of the moment, were made openly. The treaty signed by Molotov and Ribbentrop was a "treaty of non-aggression " in name only. The agreement to divide Eastern Europe between Hitler and Stalin was made in secret, hidden from the world community.

The Munich Agreement can be seen as a connivance that untied the criminal's hands; Stalin's pact with Hitler was, by contrast, a conspiracy with the criminal, with direct complicity.

Today, no serious Western historian, no sane Western politician tries to justify the Munich Agreement or the damaging role it played in leading to the Second World War.

By contrast, the assessment of the Soviet-German pact by Soviet and contemporary Russian historians and politicians is more complicated.

In the USSR, until the end of the 1980s, the pact was regarded as a forced diplomatic maneuver that allowed the Soviet Union to postpone Hitler's aggression for two years and better prepare for war. However, the events of June 22, 1941, and the military catastrophe that followed, demonstrated the inadequacy of this argument.

The role played by this "maneuver" in the outbreak of the Second World War was concealed. As for the secret additional protocol to the Pact, the USSR completely denied its existence, declaring the document discovered by the Americans in the archives of the German Foreign Ministry to be a forgery.

The actions of the Red Army in September 1939 were not considered in the context of the Second World War, but were described as a "liberation campaign" aimed at "reuniting the peoples of Western Belarus and Western Ukraine with their Soviet brothers."

It was not until the years of Perestroika that the pact and its consequences were seriously discussed. On December 24, 1989, the Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR officially admitted the existence of the secret additional protocol to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and provided a proper (though not yet complete) historical and legal assessment.

In today's Russia, these assessments are being revised again. The Soviet-German treaty is no longer called a "forced maneuver" but a "triumph of Soviet diplomacy", while the existence of a secret agreement between Stalin and Hitler on the division of Eastern Europe is no longer denied, but is openly included in the so-called triumph.

The debate over facts is basically over. But the dispute over assessments is resuming, and attempts to whitewash the USSR's aggressive policies and the state's crimes are intensifying. On the part of the Russian authorities, this dispute is being conducted in the accustomed manner: massive propaganda campaigns, criminal prosecution of dissidents, judicial farces, such as the recent trial in Petrozavodsk about "the Finnish genocide against Soviet citizens", the demolition of monuments to the repressed Poles, Lithuanians, Germans, Finns and other foreign citizens who died on the territory of Russia.

* * *

The Nuremberg Tribunal was established to prosecute the major war criminals of the Axis powers, and therefore could not consider the crimes of other actors.

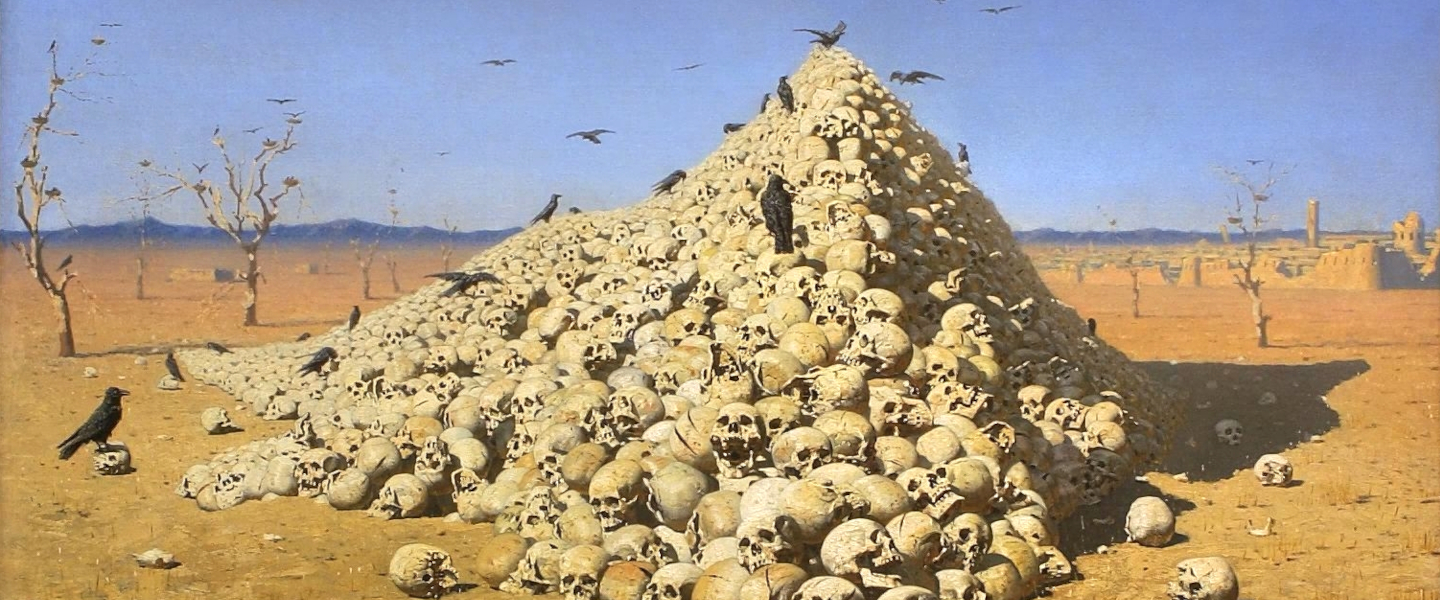

But on the basis of the legal provisions formulated by the Tribunal, Stalin and his associates should certainly be recognized as war criminals – and for the very same offenses. This includes the attack on Poland, the unleashing of the war against Finland (for which the USSR was expelled from the League of Nations), the occupation of the Baltic States, the Katyn crime – the execution on Stalin's orders of nearly twenty-two thousand Polish citizens held in camps and prisons, including more than fourteen thousand prisoners of war. These are all crimes committed during the Second World War.

The lack of clear statements by the international community on these issues has so far contributed to the re-emergence of an archaic principle, according to which "no victors are judged". Especially in countries with authoritarian and dictatorial regimes.

Obviously, this is a threat and a challenge to all of humanity. We can only hope that the international community will finally come up with a mechanism to address the issues that, for historical reasons, were kept outside of the framework of the Nuremberg Tribunal.