«I wanted to live, not play a role». Soviet trans history

Trans history in the USSR has been a blind spot for a very long time. In many ways, it continues to be so. The history of homosexuality seems to be more well-known, more apparent; it comprises the highs of increased acceptance and the repressions that followed, the history of punitive psychiatry, using homophobic legislation for repressive purposes, and so forth. At the same time, trans history takes a back seat. In some cases, it is lost within the history of homosexuality, the practices of gender dissent being entirely explained away by sexuality, despite evidence of more. In other cases, the connection with intersexuality prevails, and trans testimonies are hidden within academic articles on endocrinology and psychiatry.

This way, trans memory stays in the same limbo that categorized trans lives in the eyes of the law, society and medicine. However, there are stories that we can tell from within this space of uncertainty and vulnerability. In the era of increasing repression all around the world, the “anti-gender movement”, the interpretation of being trans as “a or as entirely antihistorical in general, becomes one of the leading arguments for the propagation of transphobia. This is why trans histories from a time and place that is perceived as entirely closed off become even more important.

One of the first mentions of trans lives in the context of the USSR can be found in the journal of the Ministry of Justice in 1922. A certain “worker of one of the offices changed into male dress, changed her name to Evgeny and married her female coworker.” The justice system did not know what to do with him. On the one hand, they felt like it was necessary to punish him, but nobody knew how. The author of the article, known only as G. R., arrives at a conclusion that is strikingly similar to modern transphobic and homophobic rhetoric. He needs to be punished in order to “prevent the public and open manifestation of her abnormal tendencies that can be detrimental to young or unstable people”.

Nevertheless, Evgeny’s marriage was not annulled. The People’s Commissariat of Justice ruled it to be consensual.

n 1926, the Circular №146 by the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) “On the Handling of Records in Birth Registry Books of Sex, Name, and Surname of Hermaphrodites” was adopted. Aimed initially towards intersex people, this law could be used by trans people as well. For a while, transsexuality was called "," which led to a small, difficult, but nevertheless real opportunity to legally change one’s name and gender marker.

There is very little data on trans history from the early 1930s to the 1950s. There could be multiple reasons for this, including heightened repression (in particular, the anti-sodomy law; we have already mentioned that transsexuality was often conflated with homosexuality), the context of the war, etc. Despite that, even then, there were cases of legal recognition. Sometime in the 1940s (the actual date is unknown), a woman known as K. K. D., who suffered for a long time due to “the uncertainty of her sex,” managed to obtain the permission to change her name to a feminine one, the right to wear feminine clothing and not serve in the army, despite exhibiting no physical signs of intersexuality.

Dusya and Andrei: being trans in the 1950s and 1960s

We know very little about being trans in the gulag. One such case is written about in Aron Belkin’s “The Third Sex.” In 1951, working as a psychiatrist in one of Siberia’s large camps, he met Dusya.

…When I did everything I needed to, one of the local higher-ups asked, “Do you want to see our Dusya?”

The mention of a female name in a male prison sounded weird. What was even weirder to me, however, was that a man was calling himself by that name. I learned his story. He was imprisoned a couple of years ago for some lesser offence. “I’m Dusya,” he told everyone, and tried to look as feminine as possible.

One of his neighbors in the barracks was a young, handsome man. Soon, everyone knew that he was Dusya’s husband.

One time, the “husband” did something wrong, and the warden beat him hard. He did not survive his injuries. And soon enough, the warden responsible for his death was found dead too. A long investigation was not necessary. Dusya did not even try to conceal what he did.

They showed him to me as a sort of local celebrity. Everyone thought he was crazy, a harmless fool, but the general attitude towards him was almost kind. [...] If someone yelled out, “Dusya!” he would come running, beaming at them. He found particular happiness in thinking that people around him considered him a woman, and was happy to be kind back. Although teasing him by calling him, as is right, , was dangerous, and everyone knew that. [When that happened], his meek soul became engulfed in the same unbridled fury that had already driven him to kill once.

The question of transsexuality started to become topical in psychiatry in the 1960s. The traditional practice of explaining the “patients’” problem through psychosis or schizophrenia became less and less attractive, considering, in particular, the small but real cross-pollination of ideas with the West.

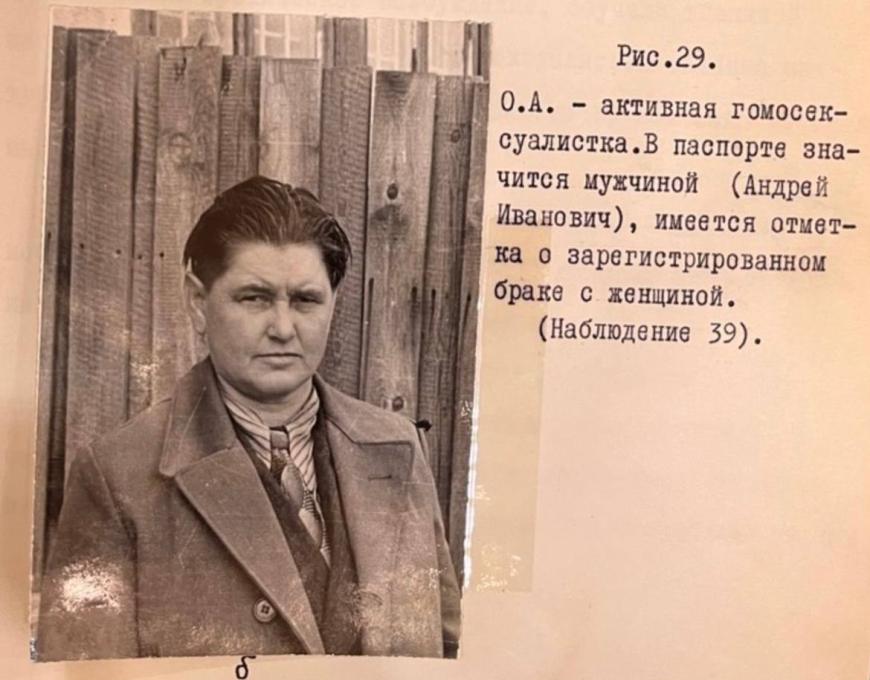

We see another case of name and gender marker change in Elizaveta Derevinskaya’s dissertation on the topic of “female homosexualism.” Andrei (called a woman in the text) somehow changed his documents and registered a legal marriage with his wife. During the psychiatric and physical evaluation, he demanded to stay on the male floor of the hospital and refused invasive genital inspections (which were, nevertheless, conducted under anaesthesia). Three years after his participation in the research project, he lived happily with his wife, worked as a security guard and was preparing to move to a different city to be with his wife’s family.

Neither Andrei nor, likely, the author of the thesis knew that less than five years were left from the moment of the text’s publication to the first successful “complete” complex of gender affirming surgeries. And this was to happen in the USSR.

“Do you know who you’d look like? … Solzhenitsyn!”

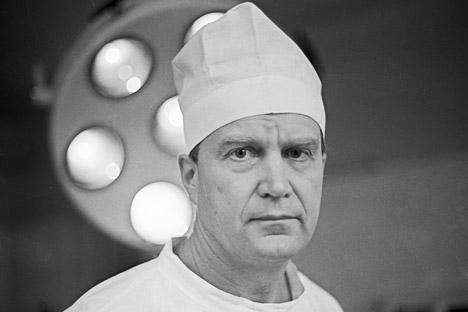

In 1968, trauma surgeon Viktor Kalnberz received a letter from his friend, biologist Vladimir Demikhov. The latter was approached by a “woman who decided to become a man.” Demikhov was famous for his unique experiments, like his dog head transplants, which is why the patient approached him first. However, Demikhov did not have formal surgical training and thus could not operate on people.

This is what the patient, whose name was Innocent, wrote to Kalnberz:

From the earliest days of my childhood, there was a deep conviction in me that I was a boy, and this boy would, in time, become a man. [...]

I am in a worse position than a spy behind enemy lines. A spy at least knows that there will be a time when he will be replaced by someone else and live like himself again. I have no hope that someone will save me from constantly living behind a mask, playing a role that I hate, wearing clothes that I detest, and being ashamed of myself even when I’m surrounded by my loved ones. [...]

I plead with you to help me get out of this hole, live at least a little in harmony with my internal needs. Live not like an outcast, but like a person among people.

It took two years of consultations and conversations with psychologists and lawyers to not only get the green light to operate, but at the very least, understand what the green light would look like. Kalnberz remembers his uncertainty, “I talked to a priest, too. I didn’t want to become anathema. The priest absolved me of my thoughts of sinfulness. Overall, there were many doubts. Everything was new, and I was about to walk into uncharted lands.”

13 surgeries took two years. In the end, they were successful. In 1972, Innocent sent the following letter to Kalnberz:

Dear Viktor Konstantinovitch!

I thank you for everything that you’ve done for me. [...] The duality that tortured me for years is finally gone. I can live around people legally. All my dark thoughts are in the past. I feel fantastic! Like a person who just woke up, I feel lust for life.

However, this “miracle” (this is how Innocent calls his surgeries) turned into fear and persecution for Viktor Kalnberz. Boris Petrovsky, the USSR Minister for Health, who used to be almost a father figure for Kalnberz, shunned and judged him. This is how Viktor remembers it:

He called me to come to Moscow. The conversation was hard; it took many hours. Petrovsky used the formal “you” to refer to me. “You’re a criminal, your place is behind bars. The Minister for Justice, Terebilov, is looking into you — you mutilated a perfectly healthy woman.” And so on. Finally, he asked me, “Do you know who you’d look like if you didn’t wash or shave for two weeks?” “Boris Vassilyevitch, I have no idea.” “Like Solzhenitsyn!” His name was like a curse word for him. “I know who put these ideas in your brain. That Demikhov knows nothing but to transplant dog heads to their asses.” What a dialogue.

The group from the Serbsky Institute in Moscow, sent to Riga to assess Kalnberz’s actions, however, did not come to the conclusion that Petrovsky expected. They considered the surgery to be successful, even though one of the members acknowledged that at the start, he wanted to assess the “psychiatric competence” of Kalnberz himself. The other directive for the group — to let the Latvian Communist Party officials know of the assessment — led to paradoxical results. Alexander Drizul, who headed the ideological work of the Party, could not understand why people were telling him about the surgery. This attempt to persecute Kalnberz ended with the members of the group congratulating him on the success of his unique surgery.

But Kalnberz did not have the chance to repeat his success. Despite the lack of a formal conviction, he received a reprimand from the ministry for a surgery “unacceptable in the USSR” and conducted “without permission from the USSR Ministry of Health.” Together with the reprimand, Viktor received a patent for his surgery, but he was forbidden from performing it again and even talking about it openly.

"The transsexual often acts more catholic than the pope himself"

The academic interest in transsexuality in psychiatric and endocrinological studies continued to rise throughout the 1970s and 1980s. While trans people in society were virtually unheard of, academic articles help us confirm not just their existence as complete outliers, but as a group. For instance, at least 176 people (if we consider respondents to have participated in every article) were mentioned in just Aleksandr Bukhanovskii’s work (if we posit that there were no repeats, the number of people that Bukhanovskii had seen exceeds 350 people). If we note that these are only people who were interested in being examined, willing to talk to doctors, or simply just aware of this opportunity, we can come to the conclusion that the real numbers were much higher. Remembering the stories of people who lived in hiding or changed their documents outside of the legal pathways, we can only imagine how many people lived their lives without ever being noticed by psychiatrists or investigators.

Here, however, we should return to the idea of demonstrativeness that we have previously mentioned when talking about Yevgeny. In his “The Third Sex,” Aron Belkin talks about his experience helping intersex people, but devotes some time to trans people as well. It is this demonstrativeness that the author finds deeply flawed, which becomes the defining characteristic of trans people for Belkin. In comparison to intersex people, whose suffering becomes righteous due to being “biologically justified,” the plight of trans people is considered almost frivolous. The desire to better their lives through HRT, gender affirming surgeries or legal recognition, the assertiveness that trans people exhibit (the hope that a doctor can not only listen, but do something) — the active fight against circumstance devalues trans suffering in his eyes, makes it fake and cartoonish. In particular, the desire to live according to their gender is described as the highest level of pretence.

This is where the imitation of appearance, behavior and manners comes from. In it, the transsexual often acts more catholic than the pope himself. Getting his appearance to an almost grotesque level of imitation, he doesn’t tickle his own ego, but rather extorts approval and support from others.

Belkin’s goal to find a way to “eradicate transsexualism entirely” is clear. But this search, as was clear even then, is futile. For instance, all of Bukhanovskii’s patients who went through the process of medical transition turned out to be “full-fledged working members of society.” Formally, Belkin also arrived at this conclusion. In 1991, in co-authorship with Alexander Karpov, he wrote the “Methodological Recommendations on the Change of Sex” from the USSR Ministry of Health.

The “Trans Thaw” and its end

In 1997, the Russian State Duma passed a law “On the Acts of Civil Status” that allowed, among other things, for legal gender and name to be amended based on a “document of the established form about the change of sex issued by a medical organization.” The formalization of this process was not instant, however, and until 2018, the procedure continued to be very opaque and long. 2018 brought change, formalizing the procedure to include only a special assessment.

This format of legal and medical transition survived only 5 years. In 2023, repressions, particularly those aimed at LGBTQ+ people, ramped up due to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The State Duma adopted a law completely banning any legal way to transition in Russia. In particular, the bill prohibited legal name and gender marker change, gender-affirming surgery, marriages and adoptions for trans people. Thus, the ability for trans people to exist legally in harmony with their gender identity survived for a little less than a hundred years.

Currently, nobody can legally transition in Russia. The so-called “LGBT movement” is considered extremist, foreign and dangerous. This is why we are remembering not only the marginal, repressed and often invisible status of trans people in the USSR and Russia, but also the stories of life lived well, despite it all.

Innocent continued to be in contact with Viktor Kalnberz. The last known phone call between them happened in 2010. Innocent was widowed and married again. At the time of their last conversation, he was older than 70. We don’t know what they talked about then. That is why we’re concluding this text with his last published letter.

Dear Viktor Konstantinovitch!

Some time passed since the moment my new, independent life had started. It was not an easy time. The danger of being found out hung over my head like the blade of an executioner’s axe. When I finally managed to conquer this fear, everything fell into place, all at once. I just live and work, like everyone else. Although not exactly like everyone else. Others see life as a constant struggle for success. For me, this struggle does not exist. I value what I think only old people value. Life itself.

Even if everything did not end the way it did, I wouldn’t have anything but the highest level of gratitude for you. Nobody in the world, except for you, wanted to help me. You took pity on me, and you acted on it. You were the only one who understood that I desperately needed change, not to spend my nights with someone I’m not supposed to, but to get rid of this terrible internal duality. You offered me otherwise, of course — change my dress, change my documents, and I could live with anyone I wanted. But I wanted to live, not play a role, even if I were wearing a new costume. I wanted harmony between my internal world and the world outside. And now I live. I taste life, and I feel drunk on its simplest aspects. The crunch of snow underfoot, the starkness of the sky above, the smell of soil and grass, the soft rustle of the sea. Everything that life is full of and rich with. Before, my internal struggle made everything quiet and far away, stripped me of all earthly happiness. Now I am happy. I achieved internal peace. I am even loved. Maybe someone will find it weird — so many people who are complete from birth cannot say that about themselves. My woman knew men before me, outwardly more masculine, but she says that she never felt as good as she does with me. I think it can be explained in many ways because, after going through my torturous journey, I cannot even think of hurting her by being unkind, inattentive or rude. Not least in my life are the care for her happiness and the tenderness I have for her. The soul is very important in many things. In love, in particular. And maybe, my soul, one that went through so much, has no competition in this area.

That’s it. My confession is over. Thank you for everything, my dear human. There is no soul in the world that will love you as loyally as mine, healed by you.

Your former patient.

January 1973

Sources:

- Белкин, А. И., и Карпов, А. С.. Транссексуализм (методические рекомендации по смене пола). М.: Министерство здравоохранения СССР, 1991.

- Белкин, А. И. Третий пол. Судьбы пасынков Природы. М.: Олимп, 2000.

- Бухановский, А. О. “О клинике и социально-психологической реадаптации и реабилитации больных транссексуализмом.” Актуальные проблемы пограничной психиатрии. Тезисы докладов Всесоюзной конференции, Витебск, 1989, стр.: 27-30.

- Г. Р. “Процессы гомосексуалистов.” Еженедельник советской юстиции, 33, 1922, стр.: 16-17.

- Деревинская, Е. М. Материалы к клинике, патогенезу, терапии женского гомосексуализма. Дис. … канд. медицинских наук. Караганда, 1965.

- Киселева, А., и Белова, С.. “Зачем Госдума приняла закон о запрете смены пола.” Ведомости, 14 July 2023, www.vedomosti.ru/society/articles/2023/07/14/985428-gosduma-prinyala-zakon?from=copy_text

- Песляк, А. “Виктор КАЛНБЕРЗ: Я первым в мире сделал из женщины мужчину.” Медицинская газета, 99, 2011.

- Сердюков, М. Судебная гинекология и судебное акушерство. М.: Медгиз, 1964.

- Фаст, Т. “13 шагов. Рассказ о серии уникальных операций, в результате которых женщина стала мужчниой.” Литературная газета, 38, 1989, стр.: 11.

- Эдельштейн, А. О. “К клинике трансвестизма.” Преступник и преступность. М.: Мосздравотдел, 1927.

- Healey, Dan. “Evgeniia/Evgenii: Queer Case Histories in the First Years of Soviet Power.” Gender & History, vol. 9, no. 1, Apr. 1997, pp. 83–106.

- Healey, Dan. Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent. The University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Kirey-Sitnikova, Yana. “‘You Should Care by Prohibiting All This Obscenity’: A Public Policy Analysis of the Russian Law Banning Medical and Legal Transition for Transgender People.” Post-Soviet Affairs, Informa UK Limited, July 2024, pp. 1–20,

- Kirey-Sitnikova, Yana. “Using the Past to Save the Present: Soviet Transgender History and Its Implications for Present-Day Trans Rights in Russia.” Kritika, vol. 26, no. 1, Slavica Publishers, Jan. 2025, pp. 189–202.