published: 18 May 2024

History of Crimean Tatar Resistance

2024 marks the 80th anniversary of the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, a crime perpetrated by Stalin’s regime. This is indeed a mournful date, particularly dark because repressions against Crimean Tatars continue to this day, arguably as a direct follow up to the Soviet period. Activists call this a “hybrid deportation.”

Table of content

After the Deportation

1944

Deportation of Crimean Tatars from Crimea

1956

April 28: Decree “On lifting restrictions on special resettlement of Crimean Tatars, Balkars, Turks – citizens of the USSR, Kurds, Hemshils, and members of their families, resettled during the Great Patriotic War”

After they were deported, Crimean Tatars, were forced to live under special settlement regulations. Residents of special settlements did not have the right to leave the territory of their locality without a permission from the head of the NKVD special commander’s office. Any changes in a family’s composition also had to be reported. During the deportation, residents of villages, often entire families were deliberately resettled to different locations to prevent them from reuniting and helping each other. These regulations made it impossible to see relatives living outside a particular resettlement. Attempts to escapes or any violation of theses restrictions would be punished with prison camp sentences. .

On April 28, the Presidium of the USSR issued a decree “On lifting restrictions on special resettlement of Crimean Tatars [...].” The abolition of the special resettlement regime allowed many to reunite with their families and move to large cities in search of work.

However, while removing administrative supervision of Crimean Tatars, the Soviet regime did nothing to rehabilitate them, nor did it drop accusations of betrayal of the Motherland, or allow them to return to Crimea.

When in January 1957 a number of repressed ethnic or national groups, who had previously been granted a “nationality” status, were given certain autonomy rights, Crimean Tatars were left deprived of such rights.

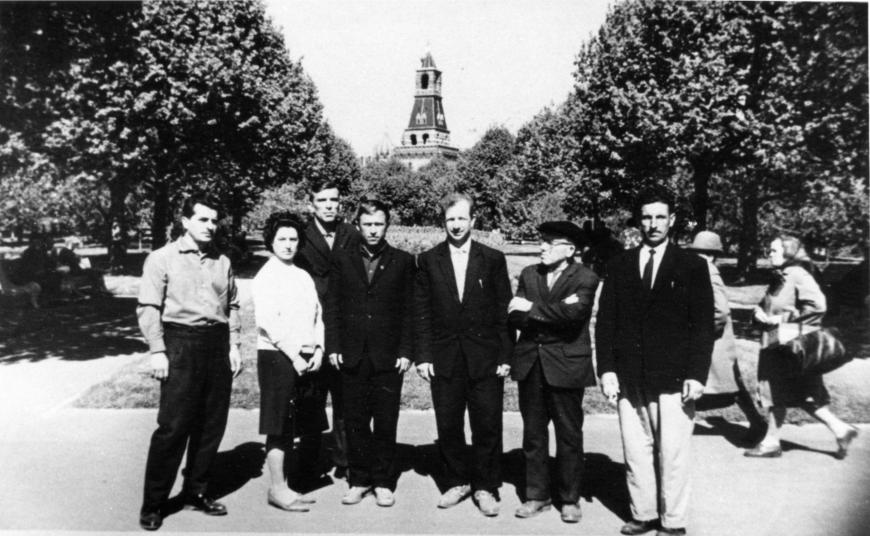

November 17: The first meeting of the underground organization of Crimean Tatar students at the Tashkent Textile Institute

The core group of the first organization of Crimean Tatars, whose meetings were attended by up to 200 people, was made up of students of Tashkent universities. Among them Sharif Bakhtyshaev, Alie Velieva, Shevket Kadyrov, Seit-Amet Muratov, Zakir Mustafaev, Rustem Nagaev, Aidyn Shemji-zade. The organization disbanded itself in 1958–59.

1957

The first delegation of Crimean Tatars in Moscow submits a petition to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR with 14,000 signatures

Throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, delegations of Crimean Tatar communists went to Moscow with letters signed by thousands of Crimean Tatars. These petition letters expressed a loyalty to the Soviet system and the hope that Soviet authorities would return to Leninist era policies and correct the “mistakes of the cult of personality” period, by allowing Crimean Tatars to return to Crimea. In 1957, such a petition collected 14,000 signatures, and in March 1961, a letter with 18,000 signatures was sent to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The letters and statements received no response from the authorities, except for repressions against the delegates who had gone to Moscow: they were dismissed and expelled from the Communist party.

The New Wave

By the early 1960s, the petition campaign subsided: people saw that it had not brought results and started losing hope. The movement was given a new impetus by young Crimean Tatars, who grew up in exile and saw the deportation not as an incidental mistake committed by the ruling party, but as part of its colonial policy. As data was collected on the number of deaths caused by the deportation and with a growing understanding of the scale of the tragedy, people started calling it a “genocide.”

1961

The first public trial of Crimean Tatar activists

The trial of Enver Seferov and Shevket Abdurakhmanov was the first political trial of Crimean Tatars in the USSR. They were accused of distributing leaflets among the residents of Chirchik, Fergana, Namangan (Uzbekistan), and Sukhumi (Georgia), on behalf of the Union for the Liberation of Crimean Tatars. On October 11, at a closed hearing at the Tashkent Regional Court, they were sentenced to respectively 7 and 5 years detention in strict security camps under Articles 60, part 1, and 64 of the Criminal Code of the Uzbek SSR: “anti-Soviet propaganda and activism” and “incitement of national hatred.”

The appeal of the Union for Liberation to the Central Committee of the CPSU was formulated in unusually straightforward terms:

GENTLEMEN COMMUNISTS!

We have endured and waited for your mercy for a long time. How long can our humiliation last? This is tragic madness and barbarism in the 20th century. For 16 years, without trial nor investigation, our people have been scattered throughout the Soviet Union. Does an entire people, without exception, children and elderly included, have to bear responsibility for the crimes committed by a handful of traitors? Even those who really fought against you with weapons have already atoned for their guilt.

Are our people worse than others? Of course not. And you know and understand this perfectly.

[...] Crimea is ours, and sooner or later you will acknowledge it. Today we have one goal: Homeland or death, and you will soon feel it. The responsibility for everything that has happened lies entirely with you.

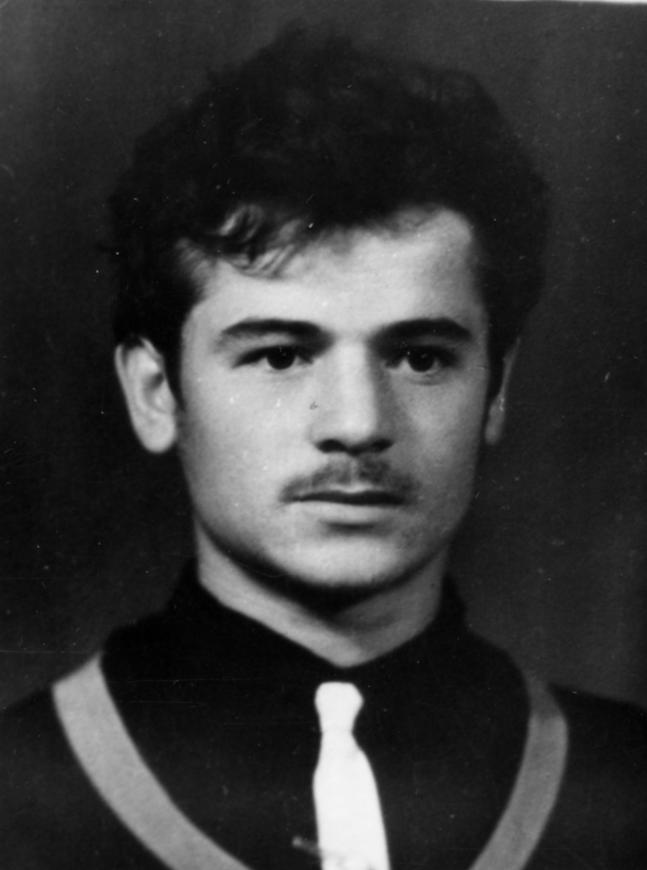

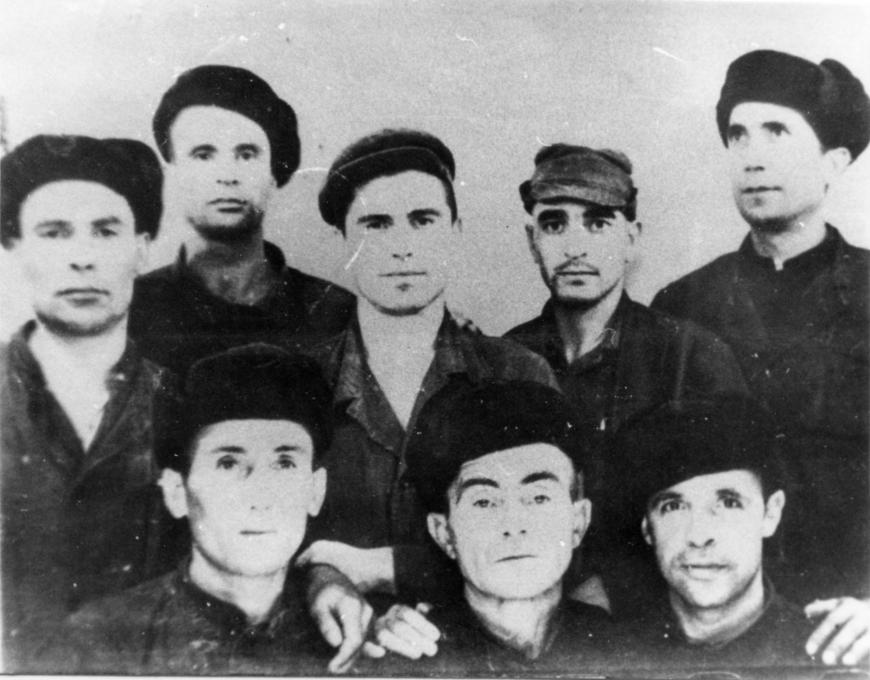

Spring 1961: Establishment of the Union of Crimean Tatar Youth

As an organization, the Union of Crimean Tatar Youth managed to exist for a very short time: its key participants were arrested a few weeks after their first meetings, even before the official charter was drafted. Marat Omerov, Refat Godzhenov, Seit-Amza Umerov, and Ahmed Asanov were arrested on April 8, 1962. Searches were conducted in their homes. Marat Omerov and Seit-Amza Umerov were accused of being the main “culprits”, while others were released. The Supreme Court of the Uzbek SSR sentenced Omerov and Umerov to 4 and 3 years of imprisonment in August 1962.

Many other students also suffered for their involvement: they were expelled from universities or dismissed from work, including Mustafa Dzhemilev, the movement's future leader.

1965

The first issue of “Information” – a Crimean Tatar human rights information bulletin

1966

Mass protests in Uzbekistan

The 45th anniversary of the founding of the Crimean ASSR was celebrated on October 8, 1966. Crimean Tatars commemorated it with festivities and rallies across several cities in Uzbekistan. The largest such events, in Andijan and Bekabad, gathered more than 2,000 people. Police and soldiers dispersed the crowds using force, beating participants and wielding smoke bombs, batons, and fire hoses. Several hundred people were detained for 15 days, and 17 people were sentenced to prison terms for “organizing mass disorders.”

1967

Soviet decree “On citizens of Tatar nationality, who previously resided in Crimea”

Decree No. 493 “On citizens of Tatar nationality who previously resided in Crimea” of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR appeared in the press on September 9, 1967. The decree lifted the accusation of treason, but in derogatory and offensive terms that denied the right of Crimean Tatars to autonomy.

The second decree, No. 494, allowed Crimean Tatars to settle anywhere on the territory of the USSR, including Crimea. However, it stipulated that this could only be done “in accordance with the existing legislation on employment and passport regime.” Soviet authorities were using this clause to prevent Crimean Tatars from returning for several decades to come.

Returns and expulsions

All officials refused to register returning Crimean Tatars, and without this stamp it was prohibited to live, work, or send children to schools in the region. The ethnic character of such discrimination was especially noticeable in mixed marriages. Frequently, people were denied registration and employment because of the Crimean Tatar nationality of their spouse.

Under pressure from the authorities, locals did not want to sell their houses to Crimean Tatars or employ them. But even if a deal for the sale of a house was reached, it was considered invalid without residence registration. In such cases, families were evicted from their homes, often in the middle of the night and with the use of force. Some houses were demolished by bulldozers or handed over to looters.

According to human rights activists, about 15,000 Crimean Tatars were able to get registered in Crimea from the issue of the 1967 decree until 1979, which represented less than 2% of Crimean Tatars in 1979.

This well-known photography of the eviction of a Crimean Tatar family from the village of Novoalekseevka is often captioned as illustrating the 1944 deportation.. This photo is held in the Memorial archives.

1968

March 17: Speech by Petro Grigorenko in support of Crimean Tatars

Spring 1968 marked an important new phase when the movement began to interact more closely with human rights activists and defenders from Moscow. With their help, contacts, and resources, the movement became visible at an international level. Foreign media started to write about the persecution of Crimean Tatars. A key moment came when Crimean Tatar activists connected with the dissident Petro Grigorenko who became their life-long supporter.

April 21: Mass protests in Chirchik and their harsh dispersal

On Lenin's birthday, without official authorization, Crimean Tatar celebrations were held in the city park of Chirchik in Uzbekistan. Police and soldiers dispersed these events using force, batons, fire hoses, and smoke bombs. More than 300 people were arrested and later sentenced to 15 days for “petty hooliganism.” Criminal cases were initiated against 10 of the arrested Crimean Tatars; they were sentenced to prison terms ranging from 1 to 3 years in the summer of 1968.

May 17: Protests of Crimean Tatars in Moscow

On the anniversary date of the deportation, a delegation of 800 Crimean Tatar representatives traveled to Moscow to hold a protest on Red Square against the brutal dispersal of the festivities in Chirchik. Police officers and KGB agents beat up and expelled many protesters from the capital, including women and the elderly.

Years of decline

The events of Spring 1968 influenced the attitudes of many Crimean Tatars towards the Soviet authorities, putting an end to their last illusions about the possibility of cooperating with them. The 1970s are considered by many historians as the period when the movement weakened, as many of its important participants and allies were imprisoned, and those who remained free doubted its effectiveness.

1974

May 17: An issue of the “Chronicles of Current Events”, No. 31, is entirely dedicated to Crimean Tatars

This issue marked the 30th anniversary of the deportation. It was prepared by Alexander Lavut and Lyudmila Alexeeva, and collected documents about the history of the movement.

1978

June: Self-immolation and funeral of Musa Mamut

Musa Mamut was 13 years old when his family was deported from Crimea. In 1975, he attempted to return to Crimea with his family, but they were denied registration, and Musa was sentenced to two years detention in labor camps for violating passport regulations. After this release, Musa returned to Crimea, where he was yet again charged with the same offense. When a local police officer approached his home, Musa Mamut went out into the yard, doused himself with gasoline, and set himself on fire. Five days later, he died from the burn wounds at the Simferopol city hospital.

As Crimean Tatars and Moscow human rights activists spread the news, all of Crimea learned about Musa's death, as did foreign reporters. The writer and Stalinist labor camp prisoner Grigory Alexandrov wrote a poem about Musa titled “The Torch Over Crimea,” which was widely circulated in samizdat form.

October 15: Decree of the Council of Ministers of the USSR No. 700 “On additional measures to strengthen the passport regime in the Crimean region” comes into force

The new decree of the Council of Ministers of the USSR tightened passport rules in Crimea, harshened penalties for their violation, legalized administrative evictions from homes without trial, and imposed sanctions for selling houses to Crimean Tatars. After that, forced evictions became even more frequent and brutal. If from January to October 1978, 20 Crimean Tatar families were banished from Crimea, in the three months from November 1978 to February 1979, this number had already risen to 60 families.

Perestroika

1987

April 11–12: First All-Union Conference of Initiative Groups of the Movement

This conference was held in Tashkent, in the house of the movement veteran Mustafa Khalilov. Participants wrote an Appeal of the Crimean Tatar People to Gorbachev, listing the people's demands and representatives.

July: Meetings with Okudzhava, Yevtushenko. Demonstrations on the Red Square

Crimean Tatar delegates met with poets Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Bulat Okudzhava on July 8 and 14, and both expressed support for the struggle, writing appeals to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

Crimean Tatar groups went to Red Square several times, demanding meetings with Soviet leaders. More than 500 people participated in the most numerous of these actions, which was held on July 25. After a disappointing meeting with A. Gromyko on July 27, during which he urged Crimean Tatars to be patient, new demonstrations began in Izmaylovsky Park, where more than 900 people gathered. The police beat up participants and forcibly expelled Crimean Tatar representatives from Moscow.

1989

April 29 – May 2: Establishment of the OKND at the Fifth All-Union Conference

In April 1989, representatives of initiative groups in Yangiul decided to create an Organization of the Crimean Tatar National Movement (OKND), uniting existing initiative groups. Mustafa Dzhemilev, a veteran of the movement, was elected chairman of the OKND. Essentially, it became a political party. Its main demands addressed to Soviet authorities were the recognition of the deportation as a crime under the International Convention on Genocide and the repeal of all decrees and resolutions violating the rights of the Crimean Tatar people.

The so-called Fergana group, or the National Movement of Crimean Tatars (NDKT) did not join the OKND. This part of the movement, represented by the dissident and scholar Yuri Osmanov, aimed to restore the Crimean ASSR according to Lenin's decree and was willing to cooperate with the leadership of the USSR for this purpose. The OKND, however, sought the establishment of national autonomy and was against the Soviet system in principle.

August: First tent city

Against the backdrop of ongoing registration restrictions and rising housing prices in Crimea, a tent city was set up in August in the village of Sevastyanovka in Crimea’s Bakhchisaray district. This became the first of a series of so-called “self-takeovers,” which the OKND named “self-returns.” 58 new houses for Crimean Tatars were being built there by the end of April. Thanks to demonstrations, protests, and the appearance of tent cities, Crimean Tatars managed to secure about two thousand plots of land for the construction of their homes.

According to the Crimean Oblast Executive Committee, as of May 1, 1990, there were 83,116 Crimean Tatars in Crimea, of whom 82,283 were registered. The context suggests that each registration was given to families through sweat and blood.

November 14: The USSR Supreme Council adopts the Declaration “On the Recognition of the Illegal and Criminal Repressive Acts Against Peoples Subjected to Forced Resettlement”

The Declaration provided for the full political rehabilitation of the Crimean Tatar people and the repeal of repressive and discriminatory regulatory acts. It also recognized the legitimate right of the Crimean Tatar people to return to their “historical places of residence and the restoration of national integrity.”

This decision is considered the first and biggest victory of the movement.

1991

January 20: Referendum on the transformation of the Crimean region into the Crimean ASSR

On January 20, a referendum was held on transforming the Crimean region into the Crimean ASSR. Despite the Crimean Tatars’ insistence on national autonomy, the established autonomy was territorial instead. Crimean Tatars boycotted the referendum, but its results remained in force.

June 26–30: Second Kurultai of the Crimean Tatar People

The Second Kurultai (national assembly) of the Crimean Tatar people took place in Simferopol from June 26 to 30, 1991. The First Kurultai had been held on March 25, 1917, and was dissolved on January 22, 1918, by the Crimean Regional Military Revolutionary Committee. By calling the 1991 Kurultai the “Second”, the organizers emphasized a continuity between both events.

A total of 255 delegates were elected to the Kurultai. Its principal documents were enacted: the Declaration of National Sovereignty of the Crimean Tatar People; the Appeal to all residents of Crimea; the Appeal to the Crimean Tatar People, and others. Additionally, the Mejlis – the executive body of the Kurultai – was elected. Mustafa Dzhemilev was appointed its chairman.

After the annexation

2014

February 26: Protests against the annexation of Crimea in Simferopol

The largest protest rally of Crimean Tatars, convened by the Mejlis, took place near the Parliament building in Simferopol on February 26, 2014. The goal was to prevent the Crimean Parliament from holding a session to discuss secession from Ukraine. Due to a lack of quorum, the session did not take place, and protesters went home in the evening, confident in the success of the action. The next day, Russian troops seized government buildings in Crimea.

Subsequently, Russian law enforcement officers detained eight participants of the protest and sentenced them to prison terms ranging from 2.5 to 4.5 years on charges of participating in mass riots. The head of the Mejlis, Refat Chubarov, was sentenced in absentia to six years in prison.

May 18: First ban on mourning events on the anniversary of the deportation

Since the early 1990s, mourning and car rallies had been held in Crimea every year on May 18 to commemorate the 1944 deportation. On May 18, 2014, these rallies were banned for the first time: the leadership of Russian-occupied Crimea issued a decree banning any mass events in Crimea as of May 16, 2014.

Since then, acts of Russian repression have again become commonplace for Crimean Tatars.

2016

April: Civil rights initiative Crimean Solidarity is founded

In April, Crimean lawyers Emil Kurbedinov, Sergei Legostov, and Vagram Shiroyan met with relatives of eight Crimean Tatars arrested on suspicion of organizing and participating in the activities of the Hizb-ut-Tahrir organization. Thus began the history of the Crimean Solidarity initiative, created to support political prisoners from Crimea and their families.

September 29: Russian Supreme Court declares the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People an extremist organization and bans its activities on the territory of the Russian Federation

The main pretext for banning the Mejlis were statements made by the Mejlis leader Refat Chubarov, who refused to recognize the legality of the Russian annexation of Crimea and called for the return of Crimea to Ukraine.

After the Mejlis was declared an “extremist” organization, law enforcement officers intensified the persecutions of Crimean Tatars. The Mejlis includes not only the central body but also many local branches – regional, city, settlement ones. Everyone who worked in this system and spoke unfavorably about the annexation of Crimea could now be accused of extremism. Cases of disappearances of members of regional Mejlis branches became more frequent – activists believe that this is how law enforcement agencies try to terrify them.

Since 2016, most leaders and members of the Mejlis have been forced to leave Crimea.

According to the civil rights organization Crimean Solidarity, as of April 24, 2024, there are 218 political prisoners in Crimea, of whom 133 are Crimean Tatars. 117 out of these 133 are detained on charges linking them to the Hizb-ut-Tahrir movement. They are accused of terrorism and extremist activities, and sentenced to stupendous terms of up to 20 years imprisonment for “offenses” such as discussing Islam. An independent project Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial recognizes them as political prisoners persecuted on religious grounds.

Activists call this a “hybrid deportation.” “In 1944, labeling us as criminals, Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea. Today, similarly, by calling them terrorists, extremists, separatists, people are thrown into police buses and taken to Russian prisons,” says human rights activist Mumine Salieva.

“In 1944, labeling us as criminals, Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea. Today, similarly, by calling them terrorists, extremists, separatists, people are thrown into police buses and taken to Russian prisons,”

says human rights activist Mumine Salieva.